Attending the New Horizons in Conservation Convening hosted by Dr. Dorceta Taylor and the Yale School of the Environment was so much fun! As a 2025 Yale Environmental Fellow Program participant, I got to meet, learn from and be inspired by so many new colleagues in the field of environmental justice work. So much conversation of transformation and action and the need for diverse perspectives in the struggle towards environmental justice.

In Dr. Dorceta Taylor’s opening remarks, she impressed upon us the importance of the various facets of environmental work. Panels, talks, and conversations spanned the gamut of topics and avenues of focus — policy, government, tech and data, urban agriculture, and academia. Dr. Taylor displayed a word cloud focused on the word environmental in all of the applications the program had received. There was research, policy, law, conservation, academia, journalism, ecology—to name a few. Sitting in the audience, quietly listening, I noticed the absence of words like Spirit, community, creation, or care.

I don’t think it’s an error or anything, just something to notice. The cosmology underlying this pattern doesn’t just appear when we talk about the environment. That colonial, Western cosmology undergirds our beliefs about the environment, each other, and ourselves.

This excerpt from one of my final papers speaks further on this thing called cosmology. Google defines it properly as “an account or theory of the origin of the universe.” Catch that — because the Christian account is not the only account.

When one considers the trajectory of the Western Christian imagination, one has to hold the role of historical events in shaping the development of Western theology – namely, the role of the Enlightenment. Identified as taking place from the late 17th - early 19th century, the European obsession with science and distilling the world into definable terms and categories colored the epistemology of western history from then, forward. It is not a coincidence that the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade is beginning simultaneously as scientific thought and industrialization are coming into the fore.

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. – Genesis 1:28

This epistemological positionality (the context through which we come to know the world) gives way to a reading of scripture that should suit the ends of apprehending the world through science. To subdue and have dominion are the operative words in this verse and give way to a perverted reading of biblical text that works to excuse the violence that European explorers would inflict on the world and on African Indigenous communities in particular.

Rather than argue against the corrupted reading of the biblical creation story, I wish, in this section, to juxtapose that story with other creation myths from different cultures. I will look to the creation stories of the Native American/Indigenous Anishinaabe people and Yoruba people of Nigeria, to highlight similarities and variances in interpretation and praxis.

I begin my analysis with the Anishinaabe Native peoples of the Great Lakes region of the country. Ethnobotanist, writer, and Anishinaabe descendant, Robin Wall Kimmerer recalls:

“It is said that the Creator gathered together the four sacred elements and breathed life into them to give form to Original Man before setting him upon Turtle Island. The last of all beings to be created, First Man, was given the name Nanabozho. The Creator called out the name to the four directions so that the others would know who was coming. Nanabozho, part man, part manido–a powerful spirit-being–is the personification of life forces. In Nanabozho’s form as Original Man and in our own, we humans are the newest arrivals on earth, the youngsters, just learning to find our way… Nanabozho did not know his parentage or his origins–only that he was set down in a fully peopled world of plants and animals, winds, and water.”

Just as in the biblical creation narrative, the first man, Adam/Nanabozho, is the last to arrive on the scene in the timeline of creation. Yet the story, even in these introductory details, hold a very different resonances. The language of subduing and dominion is not present in the indigenous account. Of course, biblical scholars of Hebrew and the Torah might make the argument that the original Hebrew from which several English translations are taken would suggest variances in connotation and meaning that departed from the normative Western interpretation. Yet the words subdue and dominion have done a particular epistomological and ontological work in/on the Christian imagination such that when Europeans brought the Bible to the shores of Africa and to the “New World,” they believed that they were fulfilling the instructions that God had given to Adam.

*Cosmology (how one thinks about the universe and it origins) informs one’s epistemology (way of knowing) and ontology (way of being).

As a theologian-in-training, I cannot understate the importance of a creation justice framework in navigating the work encompassed under the idea of “environmentalism”. When we talk about healing the environment, this is a spiritual conversation as much as an organizing and policy conversation.

“Healing is ecological as it is also political and cultural. Therefore, healing is liberation and liberation is healing—which implies that sin, in the most fundamental sense is an ecological disruption resulting in ecological dysfunction. It follows that ecoicde is deeply related to decide…” — George Tinker

This is why I talk so much about imagination. Not so much imagining something completely new, but more so reimagining the way that we organize ourselves and relate to one another. Re-membering our ecomemory, particularly for black and brown folk, is crucial. Remembering that “We are each other’s harvest, each other’s business. We are each other’s magnitude and bond.”1

One of the memorable moments from the conference was hearing from Shalanda Baker, architect of the Energy40 initiative established under the Biden administration, on a panel focused on energy, sustainability, and environmental justice. Baker was the Director of the Office of Energy Justice and Equity at the US Department of Energy. “47% of Black households experience energy insecurity.” The Energy 40 project was going to address that. Then came January 2025. And all that they were on the brink of achieving — getting the funding for energy resources to the marginalized communities that needed this kind of support — was swept away in the changing tide of the American political system.

From an organizing perspective, Baker’s remarks reignited the awareness of the importance of establishing networks and community while also imagining alternative approaches to struggle that think with, around, and beyond the old yet sturdy apparatus of American government. Her remarks regarding Energy40’s premature bust were hopeful. “We have to remember that this is the same system that built the atomic bomb.” So, in a way, it was never designed to work towards the end of bringing healing and justice to those who needed it. “We must, from day 1, interrogate the conditions of the systems in which we work!” In that interrogation, it becomes evident that we need a new system if we are truly to bring about the change and transformation we wish to facilitate in the world.

On the same panel, Dr. Brandy Brown talked about the need to “bridge the gap between policy and people.” That was the rub with Energy40 — the pipeline through which funding had to be allocated was old, rusty, unreliable, and inefficient. (Y’all know it takes forever and a day sometimes to get anything done when you’re dealing with the government.)

These are the questions we ask ourselves — as neighbors, organizers, and people in ministry. What is salvageable? What must be relinquished? How does memory point the way?

Nanabozho was also given instructions by the Creator. “Anishinaabe elder Eddie Benton-Banai beautifully retells the story of Nanabozho’s first work: to walk through the world that Skywoman had danced into life. His instructions were to walk in such a way ‘that each step is a greeting to Mother Earth…’” 2

Genesis 2, the second biblical creation account, offers more specificity in God’s original instruction to Adam.

God put the human in the garden to tend and keep the soil. — Genesis 2:15

Can Adam take a lesson from Nanabozho?

In Nanabozho’s form as Original Man and in our own, we humans are the newest arrivals on earth, the youngsters, just learning to find our way… Nanabozho did not know his parentage or his origins–only that he was set down in a fully peopled world of plants and animals, winds, and water.”

In finding our way, can we humble ourselves and learn from our older siblings — from the birds of the air, the atmosphere, and the depths of the sea? Can we learn from the past that marches alongside the present? Can we begin to make each step a greeting?

Joy and Gratitude

Exploring New Haven

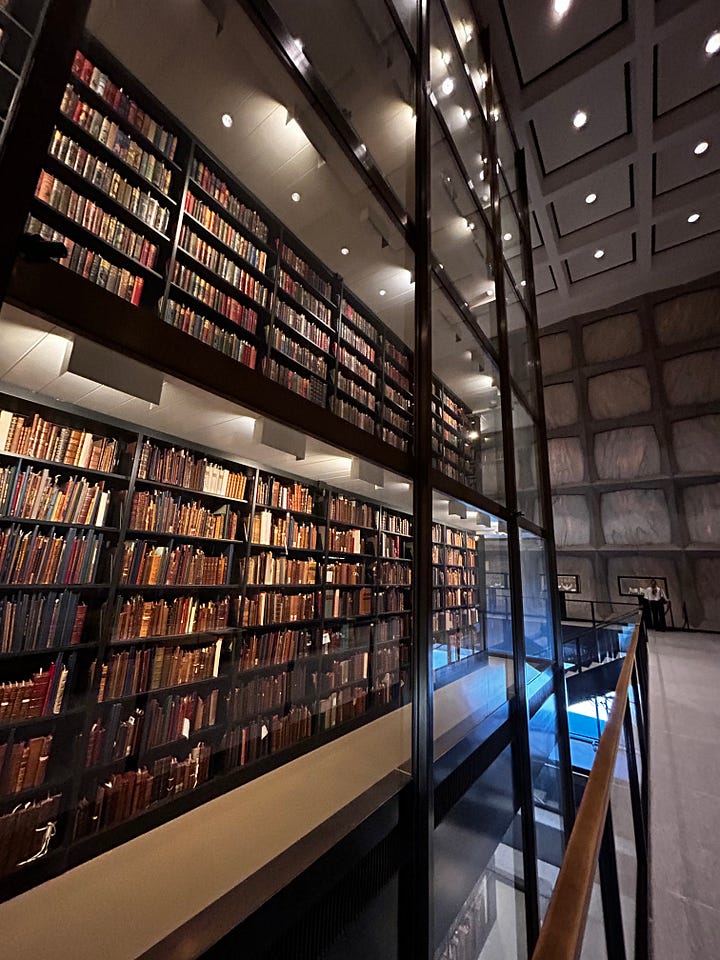

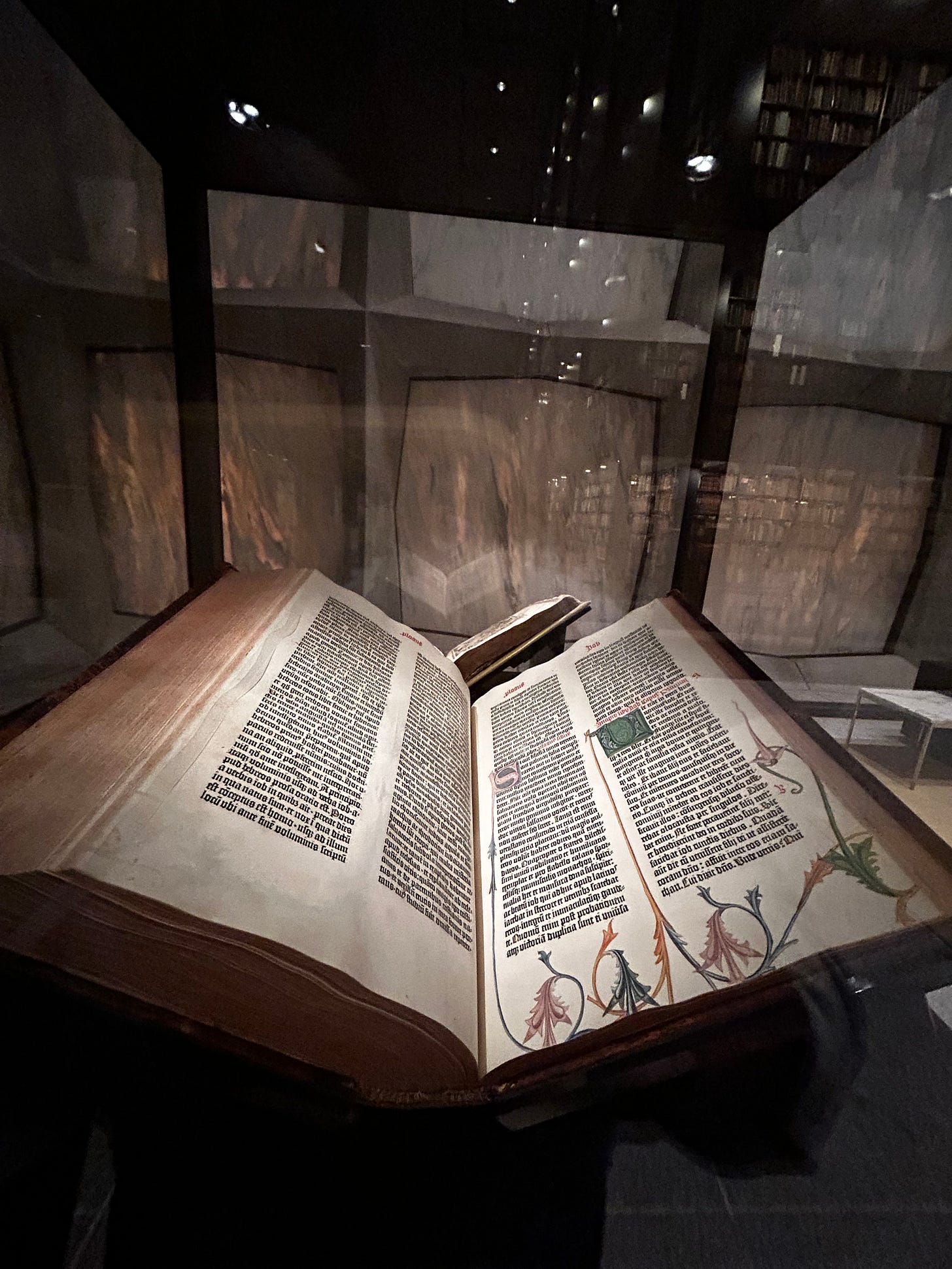

My train from New Haven back to Princeton didn’t leave until later in the evening so I took my last day to explore Yale’s libraries! My favorite was the Beineke Library of Rare Books!

It’s a beautiful facility! The architecture, the displays, the history! It’s so interesting because seeing these ancient books that are essentially math textbooks written in Arabic and also holding this thing we call epistemology and ways of knowing, the question or musing thought arises: How do we know what we know? And who taught us to know? What are the premises of knowledge — the foundational assumptions we can take for granted?

I also met some dope black farmers and learned that New Haven has a strong historically black community. Please excuse my tragically wrinkled shirt.

What the hell? I graduated?

Master’s of Theology and Ecology — check. The way I did not plan to get two master’s degrees. I came for the ecology, now I’m staying at PTS for the theology — specifically, my Master of Divinity (MDiv).

I’m excited to be spending my summer in San Francisco working at Golden Gate Parks! My housing is secured, and I've solidified travel plans. I have one final class to close out my first year of learning at PTS between now and then. Most importantly, more time to rest.

Benediction

I can no longer write, for God has given me such glorious knowledge that all contained in my works are a straw. — Thomas Aquinas

Not gonna lie, it’s now been a full year since I landed in Princeton and I’m feelin’ ole Thomas for real. Words cannot do justice to the revelations that Spirit, through this new place and these new people, has unfolded in front of me. It certainly has not been all daisies and sunshine. This year, I have grieved for things that were and were not. I have felt hurt and dealt hurt. I have harmed and been harmed. I have lamented and sank.

And I have been renewed by the trees and the chickens and the people and the air and the silence. I was/am/will be transformed. I have witnessed the gospel of the compost. Death and darkness do not have the final word.

I’ve shared bits and pieces here over the last few months. I will continue to do so, as it is confirmed that I’ll be sticking around Princeton a little while longer. I get to root a little deeper, and in so doing, stand taller.

I’m grateful for death. I’m humbled by resurrection. I’m awaiting transformation.

May the grace of God be with you and yours.

quote by Gwendolyn Brooks

Kimerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweet Grass. “Becoming Indigenous to Place”

Really loved this. Proud of you Vic! And thanks for sharing your love, light, and knowledge. 🤍

Thanks for sharing Vic! I am an interested observer of your growth knowledge. Keep enLIGHTening us.